Features

Research

Broodstock program examines effect of environment and genetics on salmon deformities

October 1, 2015 By Erich Luening

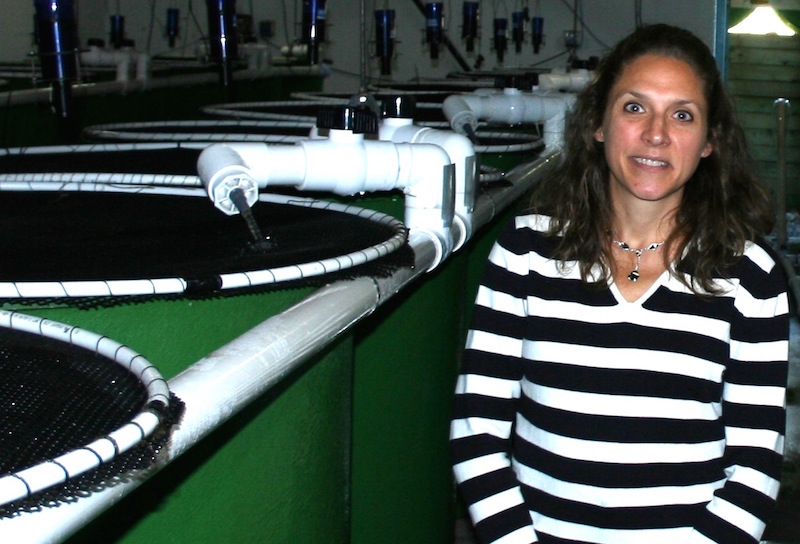

Random groups of progeny were assessed for the type and prevalence of deformity in a project carried out the Huntsman Marine Science Centre in eastern Canada.

Random groups of progeny were assessed for the type and prevalence of deformity in a project carried out the Huntsman Marine Science Centre in eastern Canada.Deformities and abnormalities are often seen in Atlantic salmon by those involved in commercial production. They may be the result of environmental conditions, but the influence of genetics is also a key factor and one that’s not well understood.

With this in mind a Canadian study to examine the effects of both environmental and genetic factors on the prevalence of deformities in Atlantic salmon has been carried out at the Huntsman Marine Science Centre in St. Andrews, New Brunswick. The data will be useful to commercial producers, showing them what relevant factors are under their control and stressing the importance of appropriate individual and family selection within broodstock programs.

The project standardizes possible impacts and environmental effects across different tanks and recirculation systems – density, feeding, temperature, saturated oxygen, pH and CO2 levels, among others. Random groups of progeny are assessed for the type and prevalence of deformities within a family. The fish are assessed for skeletal deformities such as short opercula, abnormal jaw or head and spinal curvature as well as irregularities such as eye issues and missing, short or eroded fins.

“The most comprehensive deformity dataset we have is at pit tagging, because we don’t tag any

fish that are deformed,” says the project lead, Dr. Amber Garber. “Sometimes, maybe a family that had a lot of skeletal deformity, like a scoliosis, later on pops up with some fish having scoliosis as well. Where they were smaller, we didn’t see it, but if you x-rayed the fish you would have seen it. As they grow it becomes more apparent.”

Dr. Garber and her team started to analyze the data on the absence or presence of deformities. They also looked at the data by adding deformities together – ensuring that fish with multiple deformities are so noted.

“Higher numbers of deformed individuals result in higher numbers of fish assessed,” says Dr. Garber. “If a family had a 40% deformity, we’re going to go through a lot more individuals because we want to pit tag a certain number of fish. We have more detailed information on the families that have high deformities.”

Four year classes have been assessed to date, which includes 300 families and nearly 94,000 individual Atlantic salmon. All of the recorded information is included in the analysis to determine if the prevalence of deformities can be attributed to environmental factors.

“Once we have generational information, we can say “yes, deformities within a year class may have been the result of an environmental trigger” and we can go back and try to find some variable with broodstock or early rearing that could have resulted in a higher prevalence of deformities,” says Dr. Garber.

The study, funded by the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency’s Atlantic Innovation Fund, New Brunswick Innovation Foundation Research Innovation Fund and Northern Harvest Sea Farms, was carried out at the Huntsman Marine Science Centre in St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

Though the deformity study drew to a close in September, Dr. Garber and her team hope that the broodstock development program will continue in perpetuity.

Print this page