Features

Profiles

Sunland hatchery – the saga continues

Sunland Hatchery is set in idyllic surroundings near Lake Cootharaba on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. The hatchery (established in the ‘70s) spawned Australian native species and raised them for private and public stockings, and once was the country’s largest producer of Australian bass (Macquaria novemaculeata).

June 28, 2017 By John Mosig

Readers of Hatchery International will recall the environmental problems that besieged Gwen Gilson of Sunland Hatchery and the Noosa River Catchment. Regular contributor John Mosig provides an update.

Readers of Hatchery International will recall the environmental problems that besieged Gwen Gilson of Sunland Hatchery and the Noosa River Catchment. Regular contributor John Mosig provides an update.In the early 1990s a macadamia nut farm was planted on the neighbouring property surrounding the hatchery on three sides. Part of the nut farm’s management program entailed spraying a cocktail of agricultural chemicals and Gwen started to suffer sporadic mortalities following spraying events.

In 2005, the nut grower started using a larger more powerful spray rig to cover the growth of the maturing trees, and the mortalities became constant. Gwen’s other farm animals were also suffering: poultry and livestock sickened and died, stillborn calves and foals became the norm. Her own health, and that of her employees began to deteriorate. There was no clear cause, but as the fish deaths and livestock sickness coincided with the organophosphate spraying events there appeared to be a link.

Highly respected fish health vet, Dr Roger Chong from Biosecurity Queensland, had suggested the newly hatched fry were having convulsions. Gwen, who had worked as veterinary nurse, suggested Atropine as an antidote for organophosphate toxicity. It was an effective treatment for both the farm animals and the fish larvae, but not a satisfactory solution to the problem.

Safer ground

Fortunately, Gwen was able to move her entire operation to another property beyond the reach of the spray drift, and once again produce healthy fingerlings for her customers. A rational person would expect this to be the end of the matter, but no. The findings of a science-based enquiry would have led to action from those entrusted with the protection of citizens’ rights, and of the environment. Such action would have safeguarded Gwen’s livelihood, investigated any damage to the wider environment. Not so. The matter was treated by bureaucrats who should have responded more forcefully as little more than background noise and a distraction.

But they hadn’t counted on Gwen’s tenacity, and her scientific mind. She kept meticulous records and taught herself the skills of the modern digital age. Gwen credits HI’s publication of the ‘two-headed fish’ story for the matter going viral. Her microscope shots of a two-headed fish embryo spawned from Noosa River brood-stock forced the authorities to act. The outcome? The Noosa Fish Health Investigation Task Force.

The Task Force reports

After 2½ years, in a majority opinion, the Taskforce claimed there was insufficient evidence to link a single agricultural chemical to the fish deformities and other mortalities suffered at the Sunland Hatchery and surrounding farmland. The irony is that the two people best placed to make a judgemental call on the matter — scientists trained and experienced in the field of aquatic veterinary science, Drs. Chong and Landos — recorded a dissenting opinion.

Adding further irony to the Taskforce report is that the Australian Pesticides & Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) deregistered endosulfan (one of the chemicals in the macadamia cocktail mix) for agricultural use in October 2010, stating that new information showed that the prolonged use of endosulfan “is likely to lead to adverse environmental effects via spray drift and run-off,” and that the long term risks “could not be mitigated through restrictions on use or variations to label instructions.” The US banned endosulfan in July of the same year, citing the possibility of “unacceptable neurological and reproductive risks to farmworkers” in its rationale.

The then Fisheries and Agriculture Minister, Tim Mulherin, told reporters such investigations were always complex and it was difficult to identify a specific cause, and “…there was no definitive link between chemicals and the events that occurred at the hatchery or in the Noosa River.” The Minister added, “While agricultural chemicals may be a contributing factor … other factors like fish diseases and parasites, water quality, past environmental contaminants and hatchery management practices cannot be ruled out as the primary cause.” In fact, Gwen had been breeding fish successfully at her Gilsons Road property since the late 1970s, and is widely respected for her innovative technical skills. Things only started to unravel when the macadamia spraying started in the 1990s.

No help from council

She was also abandoned by the local council and environmental movement. The Sunshine Coast owes its very existence to tourism, and its possible that the local council didn’t welcome the attention drawn to the less than pristine ambience of the region. Hatchery International approached the local environmentalists for comment and support for Gwen, but was met with indifference. A pity, because the environment they vowed to protect was and continues to be seriously compromised.

Local fisher folk, both commercial and recreational, have recognized the wider issues. The Noosa basin, where agricultural sprays end up, is (or was) an important nursery for several freshwater and estuarine species. Errol Lindsay, who has spent 46 years fishing the area said: “The fish are increasing in size, indicating there’s no recruitment, and the catches are diminishing. And it’s not just bass. Twenty years ago these lakes we full of freshwater mullet [Myxus petardi], fork-tailed catfish [Arius graffei] and bony bream [Nematalosa erebi]. They’ve all gone the same way as the bass, and we haven’t had a decent prawn season for over 15 years.”

The courts were no help

While all this was going on, Gwen was pursuing her case against the macadamia farmer through the courts for the loss of business, and the cost of having to carry out her own investigation into the mortalities. She is bound by the Deed of Settlement to restrict her comments to “The matter has been resolved without any admission of liability. A Notice of Discontinuance has been filed and the dispute is at an end.”

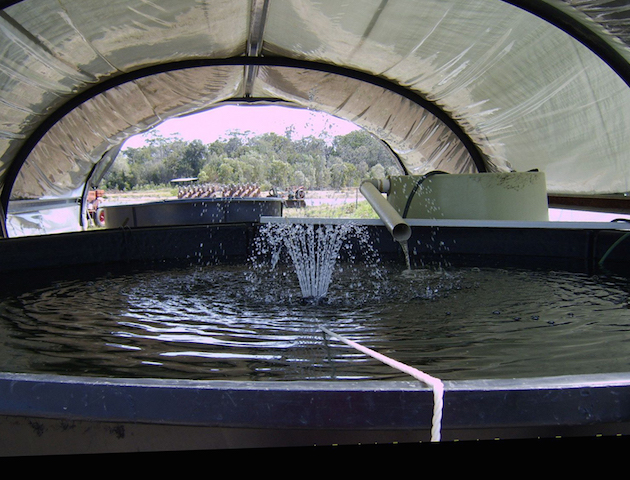

Encumbered with the debt incurred in defending her rights, and the cost of conducting her own research, she had to sell the Gilsons Road farm. The property was sold with full disclosure of its history, for around half its true value. She now lives at her Ringtail property and operates a makeshift hatchery a safe distance from the macadamia grove. She suffers health issues, for which there is no cure, from living and working at the Gilsons Road farm and has been advised by her doctor to stay away from it.

What of the larger picture?

The larger story is no brighter. Water sampling at stations throughout the Noosa system has found traces of a wide range of agricultural chemicals, but all have been below what the regulations define as threshold levels. Among the most common was Carbendazim, which has been shown to damage the development of the testicles and production of sperm in rats. It has also been shown to damage growth of mammals in utero. It was listed by the German Federal Government as a “potential human hormone-disrupting chemical” and also causes human babies to be born without eyes, exactly what the Noosa River deformed fish embryos and fry show. Once again, aquaculture is the ‘canary down the mine’ of the aquatic environment.

Is this the final chapter of the Sunland Hatchery and the Noosa River story? Hopefully no, but sadly, we can most likely anticipate more harrowing reports of environmental degradation in the region.

For more information contact Gwen on sunlandfishhatchery@bigpond.com.

Print this page